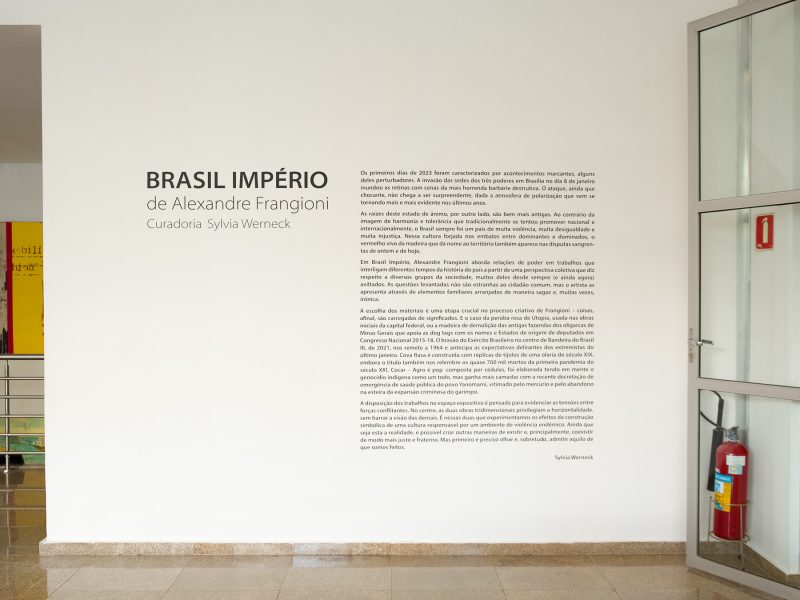

Brasil Império (Brazil Empire)

Pinacoteca de São Bernardo do Campo

February, 2023

Brazil Empire

Alexandre Frangioni

The first days of 2023 have been characterized by remarkable events, some of them disturbing. The invasion of the headquarters of the three branches of government in Brasília, on January 8th, filled the eyes with scenes of the most horrendous and destructive barbarity. The attack, although shocking, is not surprising, given the atmosphere of polarization that has become increasingly evident in recent years.

The roots of this state of mind, on the other hand, are much older. Contrary to the image of harmony and tolerance that has traditionally been promoted nationally and internationally, Brazil has always been a country of great violence, inequality and injustice. In this culture, shaped by the clashes between the dominant and the dominated, the bright red of the wood that gives the territory its name also appears in the bloody disputes of yesterday and today[1].

In Brazil Empire, Alexandre Frangioni addresses power relations through works that interconnect different periods of the country’s history, from a collective perspective that concerns various groups in society, many of whom have always been (and still are) demeaned. The issues raised are not unfamiliar to the average citizen, but the artist presents them through common elements, arranged in a clever and, often, ironic manner.

The choice of materials is crucial for Frangioni’s creative process – things, after all, are loaded with meaning. For instance, the pink peroba from Utopia, used in the construction of Brasilia, Brazil’s capital, is also the demolished wood from the old farms of the oligarchs of Minas Gerais state that supports the dog tags with the names and states of origin of deputies of the National Congress from 2015 to 2018. The coat of arms of the Brazilian Army in the center of Brazilian Flag III, from 2021, takes us back to 1964[2] and anticipates the delirious expectations of the extremists of last January. The work Shallow Grave is built with replicas of bricks from a 19th-century brickyard, although the title also reminds us of the almost 700,000 deaths[3] from the first pandemic of the 21st Century. Cocar – Agro is pop, made of banknotes, was designed after the indigenous genocide issue, but acquires more layers with the recent public health emergency statement of the Yanomami people, victims of mercury and abandonment in the loop of the criminal expansion of mining.

The arrangement of the works in the exhibition room is designed to highlight the tensions between conflicting forces. In the center, the two three-dimensional works prioritize horizontality, without blocking the view of the others. It is in these two works that we face the effects of the symbolic construction of a culture that is responsible for an environment of endemic violence. Even though this is the reality, it is possible to create other ways of existing and, above all, to coexist in a fairer and fraternal way. But first, we need to acknowledge and, above all, admit what we are made of.

Sylvia Werneck

[1] Pau-Brasil [brazilwood], the name of the tree that inspired the country’s name, was found in Brazil when it was invaded by Portugal during the 16th Century.

[2] 1964 is the year when Military coup in Brazil took place.

[3] Brazil registered over 700,000 deaths from Covid-19.